From Bikila and Hill, to Bekele and Kipchoge

60 years of Running Shoes – What difference have they made?

Kami Jogee & Adri Hartveld

This article analyses how identity and image play a greater role in the sale of trainers than performance.

It took nearly 60 years of running shoe evolution, but finally the running shoes at the front of this year’s elite London Marathon all have springy soles. World record holder on the track Kenenise Bekele is challenging world marathon record holder Enid Kipchoge in VaporFlys. After missing out on the road world record by just 2 seconds in Berlin, this battle could see another marathon world record to be broken with the help of sole technology. This will push further the enormous increase in the sales of running shoes. However from amateurs Abebe Bikila and Ron Hill in barefoot or minimalist footwear to the professionals’ spring plated footwear there has only been an increase of 0.25 % per year in marathon pace. This analysis contrasts the role of footwear in running performance with the role in image and identity, and reveals dramatic surprises.

Introduction

There is no denying that we are in the middle of a revival in the wear of trainers. Young and old are walking around in sports footwear, on the streets of almost any town and city in the world. This greater presence within more formal and everyday settings does not, however, mean that the trainer’s existence for actual sports has been diluted. Far from it. With the overwhelming cultural shift towards a ‘cleaner’ lifestyle, parks and sports halls are dominated with trainers more now than ever before. The sight of trademarked brands such as Nike, adidas and PUMA battling it out on the roads, in the parks and in the gym, is one we are most familiar with. When running shoes, and activewear in general, are at the epicentre, we need to unpick how we came to this moment. Why is it that the loafer or the sculpted stiletto, that for so long reigned supreme, are now being replaced by the cushioned padding of the overtly casual trainer?

Naturally, the footwear industry has responded to those trends. The competition in “athleisure” footwear is intense. The various brands compete in style, image, price, and functionality. Just wearing a pair of trainers that are associated with running shoes, can no longer show identity. Most individuals sometimes wear trainers, with different types of trainers possessing the power to reflect on both constitution as well as representation of individuals.

Sponsorship of athletes is based on the premise that the customer believes the top runners represent top performance, style, and image. Wearing a similar shoe as, for example the world marathon record holder Enid Kipchoge, enhances the identity of a “runner”. The feeling of being identified as an athlete, as opposed to a person that does not try to be fit and fast, is perhaps more important than the functionality of the shoes.

This historic review of marathon performance footwear makes a link between the running performances of the best athletes in the world, and the popularity and sales of running shoes. At Staffordshire University Adri Hartveld & Roozbeh Naemi – READ HERE – grouped running footwear in 4 performance concept categories:

- Minimalistic footwear, inspired by Abebe Bikila’s marathon world record in 1960, barefoot.

- padded under the heel

- padded under the heel and the ball of the foot

- plated and padded under the heel and ball of the foot, giving energy return and thus, producing a springy effect.

In 2016 Nike incorporated plates in the running shoes of the very best marathon runners in the world. Kenenisa Bekele, Brigid Kosgei and Enid Kipchoge have taken minutes off their best times resulting in world records. Nike combined millions of dollars in marketing with this breakthrough of performance at the front of the biggest marathons in the world. So far this has affected the awareness of elite runners, who have quickly converted to the Nike plated and padded footwear. Other brands are following suit with incorporating plates and increasing the padding in their shoes.

Table 1 shows the relationship between these 4 types of footwear and the era in which they were used by the best marathon runners in the world.

| Type of running footwear | era | Rate of progress in world record (seconds per year) | Improvement in pace (percentage of time per year) |

| Minimalistic (thin soles) | 1960 -1970 | 34.8 | 0.427% |

| padded under the heel | 1970 – 1998 | 7.25 | 0.093% |

| padded under the heel and the ball of the foot | 1998 – 2016 | 23.5 | 0.311% |

| plated and padded under the heel and ball of the foot (springy) | 2016 – | 26.0 | 0.352% |

Table 1. Rate of progress in Marathon world record performances 1960 – 2019

It is clear from these statistics that the rate of improvement in athletic performance is very small compared to the rate of sales of running shoe type footwear across the world. During the period of 1970 – 1998 the rate of progress was halted by the development of padding just the heel. When the developments included the sole part under the ball of the foot, a further improvement continued. Ensuring footwear is biomechanically sound for running has made a positive difference. However, this difference is small, and therefore we need to look beyond the speed performance of such footwear. When we analyse the dominant reasons for its popularity, we see that Identity and Image are much stronger factors.

Identity and Image

It would not be an exaggeration to claim that in recent years the global health and wellness industry has seen a massive surge in popularity. In fact, according to the Global Wellness Institute, the industry has grown 12.8% between 2015 and 2017 and is now worth $4.2 trillion (£3.27 trillion), representing 5.3% of global economic output. No longer do we live in an age where wellness and all it encompasses: self-care, exercise, meditation, weight-loss, etc- is viewed as an episodic or luxury activity, rather, it is now seen as an essential lifestyle value.

Unsurprisingly, brands have jumped on this rapidly growing trend, with trainer branding the most overt example. Running and walking are the more cost effective and accessible forms of exercise for people, to lead an active and healthy lifestyle. Trainer branding however goes beyond this, in its ability to mobilise forms of identification. It exists outside its mere functional use and contributes to the multi-layered process of embodied social identification.

Qualitative research studies, such as that undertaken by Jenny Hockey at University of Sheffield, have given many examples – READ HERE. One of their participants, Claire, poignantly stating: “My running shoes predate my running… I felt that I needed to do some running, so I bought some running shoes, on the basis that the expenditure would thus motivate me to go running and it did, I’ve run quite a bit since I’ve had them”. Claire’s belief that an investment in new running shoes would inspire her to run more, demonstrates not only the commercial power of trainers as a commodity, but perhaps more significantly, it shows how changing one’s shoes has the power to shift one’s identity. Claire’s new active lifestyle as a runner is tied explicitly with her new trainers. The fact that they provoked her running suggests that she sees them as being evocative of both fitness and her own ambition; to be fit and active. In this example, then, both shoe and wearer are orientated towards what is to come- they foreshadow the event. From this perspective, the trainer has played a principle role in shaping both lifestyle and identity.

Much like the cultural environment of the 1970’s, we currently live within a society that places health and fitness synonymously with enhanced attractiveness and success. Claire’s purchase of running shoes in the hope that it would ignite a practice of running is symptomatic of such an attitude, showing the rhetoric that participation in exercise is an act of bettering oneself, both physically and mentally.

Minimalist vs Springy soles

The minimalists: Abebe Bikila and Ron Hill

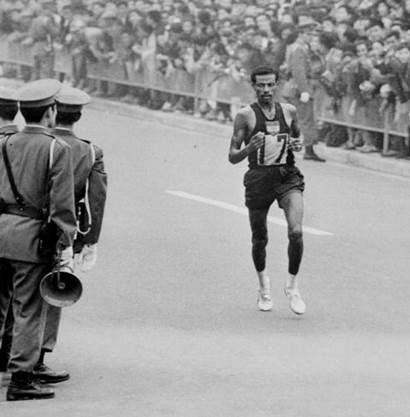

Abebe Bikila

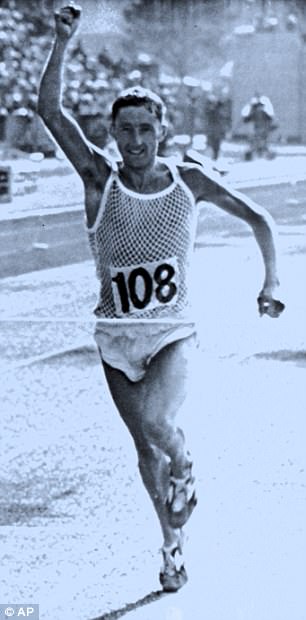

Ron Hill

On September the 10th 1960 Abebe Bikila, an unknown runner from Ethiopia, won Olympic gold for his record breaking 2 hours 15 minutes and 16 seconds Marathon run. However, more astonishing than his unimaginable pace, was the fact that he ran to victory not in any mechanically advanced trainer, but in his bare feet. Bikila’s barefoot triumph is perhaps the most famous in modern running history. His accomplishment not only secured his status as a revered historical figure but forced us to reconsider and question the limits of performance footwear. Do trainers really have an impact on performance? Or, as miraculously demonstrated by Bikila, are we better trusting in the powers of our own extremities?

When Bikila went up to take his place at the start line, his shoeless feet and skeletal frame prompted the now infamous remarks made by fellow runner Ray Puckett, ‘’Oh, well, that’s one we can beat, anyway’. Bikila soon showed, in the most overt of ways, Puckett’s judgment to be ill-fated. His display of strength and toughness was so astounding, it has become legendary. He carved out an identity for himself, one that was minimalist (barefoot, slender frame and unphased demeaner), but resilient, and hardened by miles of shoeless training on the high Ethiopian Planes. Bikila’s performance coupled with his unassuming appearance has contributed to the rhetoric that ‘minimalism’ connotes strength. On the face of it, such a connotation seems logical. Indeed, it has been common amongst competitive runners to opt for a more minimalist option in terms of footwear. Many have studied from people who live closer to nature, such as the Tarahumara Indians, whose prowess and limitations as runners are well-known in the running world.

Put simply, minimalism embodies the premise ‘less shoe, more you.’ The idea is that less cushioning and support from the shoe, means that the feet will be more engaged, and strengthened. Minimalism aimed to reconnect runners to an organic experience, one that would ultimately improve form. Here, we can see how this ‘back to basics rhetoric’ aligns itself with the idea of being tough. When one is running in such close proximity to the earth, with no substantial support between foot and ground, more strain is put on the body, forcing it to work harder, build strength and ultimately improve performance. Taking this into account, it seems reasonable to suggest that a reliance on minimalist footwear lays the foundation to make a better runner.

As previously mentioned, minimalist footwear has indeed been a firm favourite amongst competitive runners. In addition to Bikila, acclaimed English runner Ron Hill, himself a marathon world record holder, ran many of his famous races barefooted. To get to the top, Hill consistently sought out ways to train harder than any human had done so before. He is quoted as saying that after a bad race, a form of self-punishment would be to go out and ‘run a hard 20 miles’. Whilst this may seem extreme to most, it is this ‘toughness’ and determination to be the best, that has cemented the iconic status of Bikila and Hill. While running barefoot was more of a common practice in Bikila’s native Ethiopia, for Hill, training barefoot was a way to test the limits of his endurance on his relentless search for improvement. Hill raced barefooted in both the International Cross-Country in 1964 and the Mexico Olympic 10,000m, coming second and seventh respectively. Hill’s experimentation with barefoot running and minimalism similarly took place off the track as well. With a PhD in Textile Chemistry, Hill was able to combine his technical expertise and running background to produce a core range that catered to the needs of runners. A champion of synthetic materials, his ventilating mesh vests, waterproof jackets and reflective safety strips were breakthroughs. His championing of such a minimalist aesthetic therefore provides arguments promoting minimalist performance footwear- and by extension minimalist sportswear- with further legitimacy.

Since Bikila and Hill’s amazing performance, scientists have analysed the running motion and the development of muscle fibres through running training. The best distance runners have the most elastic muscles: every step the calf, quadriceps and gluteal muscles lengthen and spring back, pushing the body up and forward. However, questions remain about minimalist footwear. Does it increase the strength and elasticity of muscle tissue? Or, does the increased strain on the muscles and tendon results in a greater risk of injury to runners?

Runners with springy soles: Kenensia Bekele and Eliud Kipchoge

Kenenisa Bekele

Eliud Kipchoge

When, on the 16th of September 2018, in Berlin, Eliud Kipchoge broke the marathon world record by 1 minute and 20 seconds the world finally woke up to the potential of shoe soles to propel athletes to faster times. With Kipchoge accomplishing his achievement in Nike’s much talked about Vaporfly trainers, it seemed that the previously favoured trend of minimalist footwear had finally died down. A year later Kenenisa Bekele, the world record holder for 5km and 10km on the track, followed him on the same shoe soles and came 2 seconds short Kipchoge’s record. Bekele had already proven his superiority as athlete through eleven world cross-country championship wins. He ran these races on simple thin cross country spike shoes, as all the other runners in the races. However, with the VaporFly footwear, Bekele’s full potential as long-distance runner on the tarmac roads was showcased. He improved his personal best on the Marathon by 2 minutes and 2 seconds. By 2019, the five fastest marathons ever run all occurred in a version of Nike’s Vaporfly. What had been proven in ice speed skating with the klapschaats (clap skate), and with running for amputees with the spring blades, finally happened in distance running: energy return can be enhanced with running shoe soles. Nike’s Zoom Vaporfly’s two differentiators are the fibre-reinforced plate and the greater height of the sole. Back in 2013, Healus Ltd had already patented “Dynamic Footwear that Aligns the Body and Absorbs the Impact”, which had such plate and greater sole height. READ HERE. This invention achieved its lower shoe weight with various recesses.

Nike claims that its new footwear delivers an energy return increase of 30%. Midsoles that include such fibre-reinforced plates, can give energy return, that has similarities with the spring blades prosthetic legs of amputee runners. This then gives assistance to the leg muscles, which already provide a lot of energy return during running. In a well-trained athlete that small amount of assistance can make the difference between winning a marathon and the debilitating fatigue that weighs on the legs after 20 miles.

In the light of such technological advancement, it is no surprise that the Vaporfly shoes themselves have been the centre of some controversy. They have intensified the debate around the effect of running shoes on marathon performances, making it increasingly difficult to deny that advances in shoe technology are part of what’s driving the current surge in marathon times and the aim to complete a marathon within 2 hours. While the extraordinary capabilities of both Kipchoge and Bekele cannot be ignored, it is clear that footwear had a part to play in their record-breaking performances. This begs the question; how well do we want our running shoes to work? The latest Nike footwear prove that, soles can produce more spring. Unlike the minimalist shoes that perhaps ignites a sense of ‘toughness’ and ‘strength’, this kind of footwear, made springy through a plate and energy returning foam, promotes the feeling of bounce and lightness.

During the 2010s the image of a “real runner” and the identity of being good and clever at distance running has changed. When Bekele and Kipchoge run on springy soles, and are setting the world to light, it would appear outdated and not “in the know” to run races in footwear from the 20th Century.

Conclusion

The runners discussed in this article, from Abebe Bikila and Ron Hill to Kenenisa Bekele and Eliud Kipchoge, represent incredible talent for running as well as superb training regimes. Their achievements have not only carved them out a place in history, they elevated them to an iconic status within the world of running. We have discussed the link between performance footwear and one’s identity and image, through analysing the specific footwear favoured by these individuals.

We examined the trend of barefoot running and minimalist footwear favoured by the likes of Bikila and Hill and the image of ‘strength’ and ‘toughness’ it connotes. This contrasts to the ‘bouncy’, ‘springy’ image of Nike’s VaporFly as displayed by Bekele and Kipchoge, which demonstrates the evolution of performance footwear. Whilst we embark upon a new decade, it has become clear that the debate between the best type of performance footwear is not over. The footwear issues of both identity and performance, and the effect this has on the consumer, will no doubt continue.

Leave A Comment